The question of barefoot versus shod horses is an age-old yet ever-relevant debate, involving both practical considerations – such as hoof protection on hard ground and performance – alongside concerns for health and well-being.

The horse’s hoof is a living biological structure, in continuous growth, and subjected to considerable mechanical forces with every stride. It is essential to understand how wearing shoes, or conversely remaining barefoot, influences hoof morphology, the biomechanics of locomotion, and, ultimately, orthopedic health. This knowledge is crucial for making informed decisions regarding trimming, shoeing, and hoof maintenance. Several studies provide quantified data on these effects, upon which this article is based.

In this article:

What are the effects of shoeing on hoof morphology?

A central question in equine podiatry is how the interface between the hoof and the ground influences the structure of the hoof capsule. One might hypothesise that a shoe, acting as a rigid exoskeleton, would freeze the hoof in a constant shape. However, clinical data reveals a more complex reality: shoeing does not merely “protect”; it redirects the forces of growth and deformation.

Shape changes

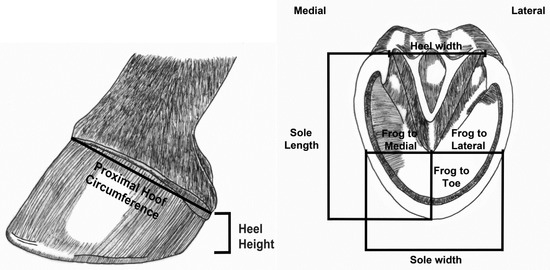

Measurements taken of the hoof

According to the study by Malone et al. (2019), conducted on 11 horses, this dynamic is now better understood. In just seven weeks, noticeable changes appear on the hoof capsule, including:

- At the coronary band: The proximal circumference of the hoof tends to narrow naturally, but this phenomenon is significantly more pronounced in shod horses. This suggests that the rigidity of the shoe at the base of the hoof limits widening, and this constraint is transmitted through structural continuity up to the top of the foot.

- On hoof angle (profile): Without shoes, the hoof tends to steepen slightly (the angle increases). Conversely, in shod horses, the hoof tends to incline more, often making the hoof profile more “run out” (shallower) over the weeks.

- Hoof width (sole perimeter): This is the most striking change. Barefoot, the circumference of the sole increases significantly; the hoof gains transverse mobility and spreads under load. Under a shoe, this perimeter decreases.

It is interesting to note that although the foot widens, its total surface area (the sole area) does not change significantly. This proves that the bare foot gains flexibility and spreading ability, rather than pure horn volume.

- Sole length: The study shows a trend toward decreased solar length in barefoot horses, though this was only statistically significant in one forelimb. This observation illustrates the process of functional wear through ground contact -a natural regulatory mechanism that shoeing interrupts. However, variability between limbs serves as a reminder that wear depends on many factors, such as locomotory symmetry, ground type, and activity level.

What can we learn from these changes?

These changes suggest that wearing shoes modifies the natural “growth/wear” cycle of the hoof, likely by limiting wall wear, altering how the hoof deforms under load, and reducing sole expansion.

Beyond these visible changes to the hoof capsule, modifications in hoof shape have direct repercussions on shock management and internal pressures. As demonstrated by Raymond Pujol (2016), shoeing is not limited to protecting the wall; it redefines how impact energy is dissipated. By modifying damping and stress distribution, shoeing imposes specific long-term adaptations on internal structures. For sport horses, this is significant: precise management of these pressures becomes an essential lever in preventing chronic locomotory conditions. This perspective emphasizes that every choice of shoeing or trimming is a therapeutic and preventive decision influencing the longevity of the locomotory system.

These observations are complemented by the work of Chateau et al. (2005), which demonstrates that shoeing, by modifying the ground interface, directly influences the biomechanics of the digital joints (fetlock, pastern & coffin). The choice of shoeing thus affects ligamentous and tendinous stresses.

In summary, neither shoeing nor remaining barefoot is neutral; each influences the shape and, by extension, the function of the hoof. Transitioning between the two requires anticipating these remodelings to preserve the long-term locomotory integrity of the equine athlete.

What does a different morphology mean?

These alterations in hoof shape impact the internal mechanics of the limb:

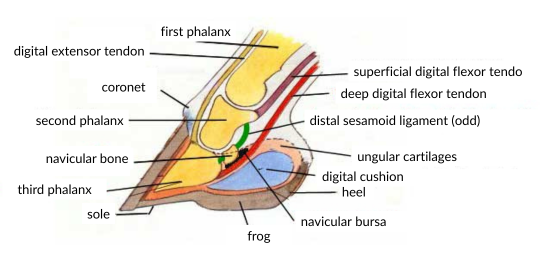

A “flatter” or less dorsal hoof angle (often observed in shod horses) modifies impact dynamics and shifts the center of pressure. This backward shift increases dorsal leverage, delaying the moment of breakover. Resulting in increased tension on the deep digital flexor tendon and higher loads on the distal joints and the podotrochlear apparatus (linked to navicular syndrome).

The more marked decrease in proximal circumference (coronary band) under a shoe indicates a restriction of global hoof expansion. By limiting this natural deformation under load, the hoof’s ability to dissipate impact energy is altered, increasing vibrations transmitted to the rest of the limb.

- Conversely, a barefoot hoof benefits from direct stimulation of the sole and frog. This interaction with the ground promotes the “hoof pump” mechanism, essential for blood circulation and proprioception. Contact between posterior structures (heels/frog) and the ground allows for a more physiological distribution of forces.

As noted by Proske et al. (2017), regular trimming for barefoot maintenance leads to durable structural adjustments: shorter walls, lower heels, and slightly backed-up toes. These are not mere horn reductions; they reorient the global angulation of the foot, allowing for more natural joint function and better distribution of compressive loads.

What are the consequences on biomechanics and locomotion?

Hoof morphology and locomotory dynamics are closely linked. Several studies have sought to quantify the impact of being shod versus barefoot on gait.

Shod versus barefoot horses: what do we learn from foot biomechanics?

The study “A preliminary case study of the effect of shoe-wearing on the biomechanics of a horse’s foot” by Panagiotopoulou et al. (2017) compared a single horse first shod and then barefoot across four types of measurements. Key results included:

- Downward and fore-aft forces exerted on the ground were nearly the same whether the horse was shod or barefoot.

- At mid-stance, the vertical force was approximately 10% higher in the shod horse than in the barefoot horse.

- Joint movements remained generally the same in both conditions.

- Finite element analysis suggested that shoeing could increase stress concentration in the distal bones of the foot (phalanges). While the study does not draw firm conclusions due to its limited sample size and modeling constraints, it serves as a potential warning signal.

In summary, while global gait may not be radically transformed -at least at a slow walk- shoeing subtly modifies force balance and load distribution. These results suggest that shoeing induces different internal stresses on the hoof’s bony structures, which could influence long-term joint health.

Stride study based on surfaces and shoe type

While we have seen that shoeing alters the shape of the foot, the question arises as to how this affects pure movement. A recent study entitled ‘Comparison of Gait Characteristics for Horses Without Shoes, with Steel Shoes, and with Aluminium Shoes’ by Gottleib et al. (2025) compared the locomotion of 12 horses at a trot, alternating between bare feet, steel shoes and aluminium shoes, on different surfaces.

The results highlight the horse’s remarkable ability to adapt. Indeed, no significant differences were detected between these three conditions in terms of locomotion symmetry, stride length or cadence (duration of the support and swing phases). This suggests that, in a healthy horse, the central nervous system compensates for weight variations to maintain a regular gait.

However, the study notes that the height of the hoof arch varies depending on the type of shoe. On both types of ground:

- The type of shoe modifies the height of the arch, i.e. the height at which the horse lifts its foot. At the beginning of the swing phase, the arch is lower with aluminium than with steel.

- At the end of the stride on soft ground, the trend is reversed with a more pronounced elevation for aluminium.

These observations demonstrate that the weight added to the end of the limb directly influences the inertia and trajectory of the hoof while the foot is in the air. Although these variations are technically measurable, further research is needed to determine whether these micro-changes alter the perceived gait.

Heel expansion and frog health

The hoof’s ability to flare out when bearing weight, particularly at the heels, is a fundamental mechanism for dissipating energy. The study, ‘Can the hoof be shod without limiting the heel movement? A comparative study between barefoot, shoeing with conventional shoes and a split-toe shoe’ by Brunsting et al. (2019) confirms that so-called ‘traditional’ shoeing significantly restricts this expansion compared to the barefoot foot. Interestingly, the use of innovative shoeing techniques, such as split-toe shoes, seems to offer intermediate flexibility, closer to the physiology of the barefoot foot.

Traditional shoe / split-toe shoe

This reduction in heel movement is not without consequences. It alters the vital functions of the hoof: shock absorption is reduced, the blood pump is less active and the distribution of forces during impact is altered. In the long term, this lack of stimulation can weaken deep tissues, particularly the plantar pad, as highlighted in the IFCE technical guide, which emphasises the need to adapt trimming and shoeing to preserve this functional locomotion.

These results suggest that shoeing, by altering the morphology of the hoof and the distribution of forces, could reduce the shock absorption capacity of the hoof itself, increasing the load on the joints or tendons. This can promote inflammation, swelling and even long-term pathologies (tendinitis, osteoarthritis, etc.).

The repercussions of permanent shoeing do not stop at the hoof capsule, but extend to the entire musculoskeletal system, as quantified by Proske et al. (2017) after 140 days of monitoring. Shod horses show relative soft tissue atrophy, with a thinner footpad than unshod horses. This phenomenon suggests that a shock-absorbing structure that is less stressed by the natural expansion of the foot gradually loses volume and effectiveness. At the same time, while the study notes slightly longer strides in shod horses, it also notes a widening of the carpal joints.

This last point is crucial: in veterinary medicine, a joint that ‘widens’ is often a sign of chronic inflammation or synovial effusion, known as synovitis. These results reinforce the hypothesis of load transfer: when the hoof, constrained by the shoe, absorbs less energy, it is the upper structures such as tendons and joints that absorb the excess vibrations. Ultimately, this change in stress distribution can promote the development of degenerative diseases such as osteoarthritis or chronic tendon inflammation.

Interpretation: barefoot vs. shod advantages and disadvantages – the contribution of EQUISYM®

Based on available data, podiatric management should be viewed as a balance between protection and natural functionality.

Cases where barefoot is favorable:

This approach allows the hoof to remain fully “active,” favoring shock absorption, blood circulation, and proprioception.

- Target: Horses not subjected to extreme constraints (soft ground, light work, leisure, pasture).

- Benefits: Avoiding the mechanical rigidity of the shoe potentially reduces vibratory stress on joints and bony structures, preserving the longevity of distal limbs. Regular trimming and varied terrain are key to success here.

Cases where shoeing is justified or necessary:

Shoeing becomes an essential ally when the environment or activity exceeds the foot’s natural regulatory capacity.

- Abrasion protection: On hard, stony, or abrasive ground, shoes protect the sole and wall from excessive wear and traumatic cracks.

- Sport performance: For intensely worked athletes, shoeing allows for precise adjustment of the contact surface. Material choice (steel vs. aluminum) and shape can optimize traction and stabilize locomotion on varied terrain.

- Therapeutic tool: For horses with anatomical weaknesses (collapsed heels, thin soles, history of pathology), shoeing—combined with orthopedic trimming—becomes a vital tool for care and prevention.

The contribution of EQUISYM® and locomotion tools

Given the complexity of changes induced by shoeing or trimming, even expert human observation has limits in perceiving micro-variations in gait. It is within this context that objective locomotion measurement tools have been developed, allowing for the quantification of movement through advanced technologies.

The EQUISYM® system is part of this approach, enabling precise evaluation of a horse’s symmetry and regularity during work. This tool allows for the objective measurement of equine locomotion using sensors placed on the horse. Specifically, it can highlight movement asymmetries that might go unnoticed during a classic examination, thereby providing a valuable basis for reflection to adapt trimming or the choice of shoeing. For a horse with an anatomical defect, shoeing can help corrector compensate for the problem.

What are the limitations on current knowledge?

Many studies feature small sample sizes, such as certain kinematic studies focusing on a single horse or only four trials, which makes it difficult to generalize results across all breeds, morphologies, and disciplines. Furthermore, research is often limited to observing locomotion at slow gaits, such as the walk or slow trot, and over short periods. This results in little longitudinal data over extended periods comparing barefoot and shod horses under varied real-world use conditions.

Modeling, such as finite element analysis, generally does not account for the hoof’s soft tissues, which play an essential role in shock absorption. While isolated bone stress data remains informative, it does not reflect the full biological reality. Finally, there are few robust clinical publications that evaluate the long-term impact on the health of joints and tendons, or the risk of pathologies such as osteoarthritis, navicular syndrome, or laminitis.

Conclusion :

Ultimately, there is no universal right answer; as is often the case, the essential factor is finding a balance. The choice between being barefoot or shod should not be reduced to dogma (“barefoot = good / shoes = bad”), but must be a reasoned and individualized decision based on the assessment of the animal, its environment, its discipline, and its history.

If the choice is made to keep the horse barefoot, regular and adapted trimming is indispensable. It is not simply a matter of removing the shoes, but of maintaining a healthy morphology with correct angles, functional heels, and an active frog.

Scientific data clearly shows that shoeing modifies hoof morphology -often by reducing its natural capacity for expansion and wear- and alters the dynamics of the forces exerted on the foot and its internal structures. However, these findings do not allow us to conclude that being barefoot is systematically “better” in all cases. It is instead a compromise, with advantages and disadvantages depending on the context. Adapted management (trimming, choice of shoe, frequency, terrain) and regular veterinary or podiatric monitoring are essential to optimize the horse’s well-being and longevity.

Appendix:

- Brunsting J, Dumoulin M, Oosterlinck M, Haspeslagh M, Lefère L, Pille F. Can the hoof be shod without limiting the heel movement? A comparative study between barefoot, shoeing with conventional shoes and a split-toe shoe. Vet J. 2019 Apr;246:7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2019.01.012. Epub 2019 Feb 1. PMID: 30902192.

- Chateau H., Degueurce C., Denoix J.-M. Influence de la nature du sol et de la ferrure sur la biomécanique des articulations digitales. UMR INRA-ENVA de Biomécanique et Pathologie Locomotrice du Cheval Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort. 2005. https://mediatheque.ifce.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=22652

- Gottleib, K.; Trager-Burns, L.; Santonastaso, A.; Bogers, S.; Werre, S.; Burns, T.; Byron, C. Comparison of Gait Characteristics for Horses Without Shoes, with Steel Shoes, and with Aluminum Shoes. Animals 2025, 15, 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15162376

- Goubault, F. G. C. (n.d.). Le ferrage. https://equipedia.ifce.fr/sante-et-bien-etre-animal/soin-prevention-et-medication/marechalerie/le-ferrage

- Malone, S.R.; Davies, H.M.S. Changes in Hoof Shape During a Seven-Week Period When Horses Were Shod Versus Barefoot. Animals 2019, 9, 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121017

- Panagiotopoulou O, Rankin JW, Gatesy SM, Hutchinson JR. 2016. A preliminary case study of the effect of shoe-wearing on the biomechanics of a horse’s foot. PeerJ 4:e2164 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2164

- PROSKE, D.K.; LEATHERWOOD, J.L.; STUTTS, K.J. et al. Effects of barefoot trimming and shoeing on the joints of the lower forelimb and hoof morphology of mature horses. Prod. Anim. Sci., v.33, p.483-489, 2017. https://doi.org/10.15232/pas.2016-01592

- Pujol, Raymond. Étude bibliographique et expérimentale de l’effet de l’amortissement des fers sur la locomotion et la prévention des affections locomotrices chez le cheval de sport. Thèse d’exercice, Médecine vétérinaire, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Toulouse – ENVT, 2016, 103 p